A D Quig reports in Crains that the City of Chicago’s Housing Commissioner says “everyone who lives in Woodlawn now should be able to stay in Woodlawn.” This can be a challenge as housing costs in the area rise. According to Crains (not corroborated by any press release I can find on web sites of the Department of Housing or the Mayor’s Office), support for housing affordabiity in the area will involve six strategies:

- Right of refusal for large apartment building tenants if a landlord seeks to sell his or her building

- Helping apartment building owners refinance properties to keep renters in place with affordable rates

- Giving grants to long-term homeowners to help with home repairs

- Financing the rehab of vacant buildings

- Setting guidelines for how city-owned, vacant, residentially zoned land can be developed into affordable or mixed-income housing

- Requiring developers that receive city-owned land to meet enhanced local hiring requirements

Details, of course, are yet to be defined, and the whole thing requires action by the City Council. Still, assuming that the program is effectively structured and implemented, what we have is the designation of a privileged class– people who live in Woodlawn– receiving benefits that might otherwise accrue to another privileged class — people who own land in Woodlawn, with a new layer of bureaucracy established (or repurposed) to administer it, including investigating and monitoring the reported income and behavior of the people who are granted permission to live in the area.

Whereas, under a land value tax, the area would now have little vacant land, presumably a lot more housing, probably quite “affordable.”

Of course if you’re the Mayor, you do what you figure is politically feasible and within your power, not what is morally right and economically efficient, but would require persuading a lot of uninformed voters and obtaining cooperation from quite a few other governmental actors.

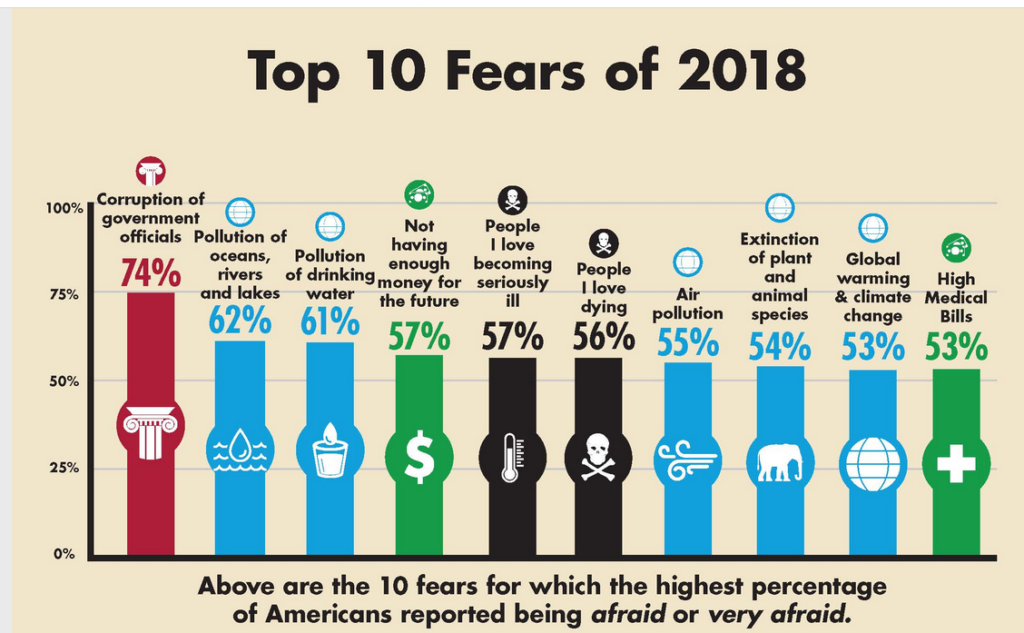

It’s pretty well-known that medical care is absorbing

It’s pretty well-known that medical care is absorbing