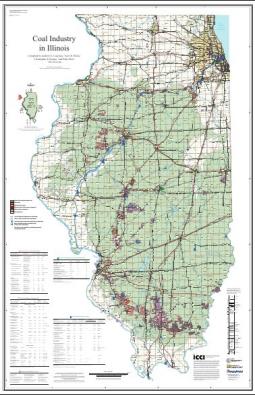

En route to writing something else, I discovered that the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability published a report last fall suggesting that Illinois might want to impose a severance tax on coal. I was surprised to learn that we didn’t already have such a tax, but encouraged that somebody is looking into it.

The report looks into severance taxes in several coal-producing states, suggesting that Illinois might raise anywhere from $1.6 million to $128.8 million, which might be shared with local governments, used as general revenue, or put into a permanent fund, or some combination. The numbers are pretty modest in the context of a state budget short by $4.6 billion for just the current fiscal year, but that’s no excuse to ignore them.

I did note a couple curious things in the report. On page five it asserts that, since most Illinois coal is consumed in other states, consumers in those states would pay most of the tax. I rather doubt that any consumers would pay it. Rather, since the coal market is national, implementation of a significant severance tax here would just reduce the value of coal deposits, so the tax would be paid by the owners or lessees of coal rights.

Second, there’s no discussion of existing real estate tax as it applies to coal deposits. Per 35 ILCS 200/10-175 it appears that coal rights, if not yet developed, are taxed on a value not to exceed $75/acre, practically a negligible amount. That’s an extremely cheap way for speculators to hold rights waiting for a price increase. But, per 35 ILCS 200/10-180, coal which is actually being mined is assessed much higher, based on its actual economic value as defined in the statute. So there’s already a substantial incentive not to mine the coal. A proper analysis would consider how a severance fee would affect this assessment, both in terms of revenue and incentives to mine or not mine.