In order to fund community needs from a tax on land value, assessors need to estimate what that land value is. Conceptually the task need not be difficult (Ted Gwartney outlines some options here, but a more complete and still-valid examination is in this book.) Basically, you look at sales prices for actual land transactions, and make adjustments for parcels which haven’t sold recently or where land comprises only a small part of the value. But what happens if the buyer pays something additional, “off the books,” for the land?

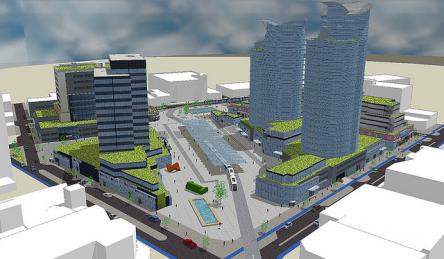

According to Peter Katz, that seems to be what often happens. This presentation at APA last March starts off slow (and self-promotional), but moves along thru some interesting territory. Regarding the price of vacant land, he asserts that, in many desirable areas, developers have to first buy (or option) the land, then negotiate with local authorities to get permission to build. Getting that permission might require agreeing to donate money (or land) for public use, or perhaps less savory expenditures, and to the developer this is part of the cost of land. If an area of any size is subject to such constraints, all the land sales are below market prices by the amount of such costs, and all sites, whether sold or not, receive assessed land values that are lower than what developers actually pay to get a buildable site. This results in less public revenue, implying a need for other taxes, as well as a tendency to develop at lower densities than might be appropriate, when developers choose to settle for existing zoning rather than what they might be able to negotiate. Katz suggests that a formal study of this effect should be done, and nominates Lincoln Institute to make it happen.

Katz’s remedy seems to be a combination of form-based zoning codes, plus a sophisticated (and presumably accurate) fiscal impact analysis that might show denser development to actually be more “profitable” to governments. But, responding to a question about 65 minutes into (and near the end of) his talk, he acknowledges that funding government from a land value tax would be a good way to obtain the desired development pattern, and that Henry George was a great guy. His observation that Georgists tend to be wacky has been made before, and I can’t say it’s wrong.