Continuing our exploration of land values and real estate taxes in Cook County …

The County contains 813 parcels coded as class 239 “non-equalized land under agricultural use, valued at farm pricing.” An explanation of how farms are supposedly assessed is included in this document, page 12 of which states:

The assessor notes each of the farm’s land use categories and uses the equalized assessed value for each soil productivity index to determine the assessed value. The assessor may make some subtractions for things like slope, drainage, ponding, flooding, and field shape and size before calculating the final value.

• The portion on which crops are planted is assessed at the state-certified equalized assessed value certified by the Department for the corresponding soil productivity index.

• Permanent pasture is assessed at one-third of what would be assigned if it was planted in crops.

• Other farmland (e.g., forestland, grass waterways) is assessed at one-sixth of what would be assigned if it was planted in crops.

• Wasteland has no assessed value unless it contributes to the productivity of the farm.

For Cook County, the Assessor provides specifics here.

The total assessed value of these 813 parcels is $2.25 million. To calculate their acreage it seems I would have to retrieve the records manually and individually, but the 2022 Census of Agriculture says the County contains 154 farms totaling 10,281 acres. (A farm might comprise several parcels). This implies an assessed value of $218/acre. Reviewing a small sample of parcels, it appears that the Assessor values most class 239 parcels at $2250/acre, and assesses them at 10% of that, or $225/acre.

One might compare this to the Illinois Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers’ report, which includes but doesn’t break out Cook County, and indicates sales prices in Northeastern Illinois range from $5500 to $40,000 per acre.

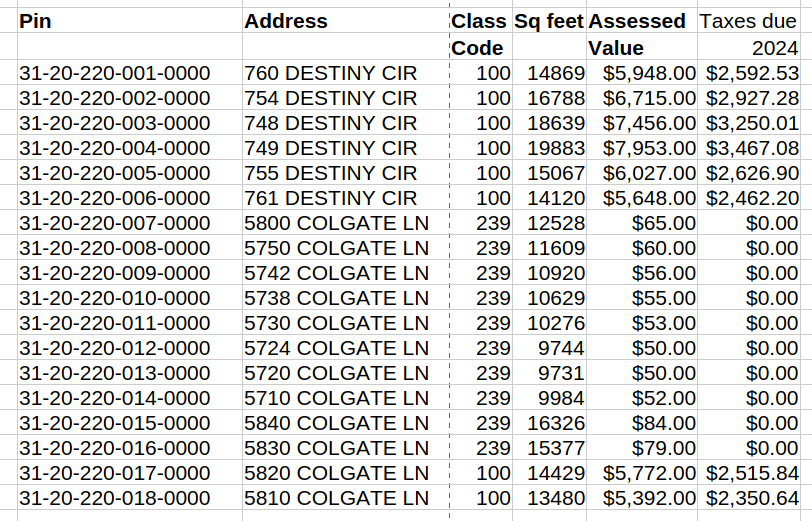

There’s no minimum parcel size for a “farm” under class 239. Thus, we have a series of 18 small vacant lots in Matteson: 31-20-218-001-0000 thru 31-20-218-018-0000. All of these appear to be empty lots, awaiting the construction of houses. Eight of them are classified as vacant land, with assessed values ranging from $5392 to $7953 (differences apparently due to differing sizes). Taxes due on these in 2024 range from $2351 to $3467 (excluding overdue taxes from the prior year, but including interest charged). But ten of these similar lots are class 239, farmland, assessed at $50 to $84. The County issues tax bills of zero for these parcels. This is claimed to be due to 35 ILCS 200/18-40, which states

If the equalized assessed value of any property is less than $150 for an

assessment year, the county clerk may declare the imposition and collection of

all tax for that year to be extended on the parcel to be unfeasible and

cancelled. No tax shall be extended or collected on the parcel for that year

and the parcel shall not be sold for delinquent taxes.

However, these parcels are assessed at $50 to $84. Applying the equalization factor of 3.0163 results in EAV greater than $150. In response to my inquiry, the Cook County Treasurer explained that, even tho equalized assessed valuation is printed on the tax bill, it isn’t used for taxation of farm properties. Here are the 18 parcels:

I don’t know why 10 of these properties are assessed as farmland while 8 are not.

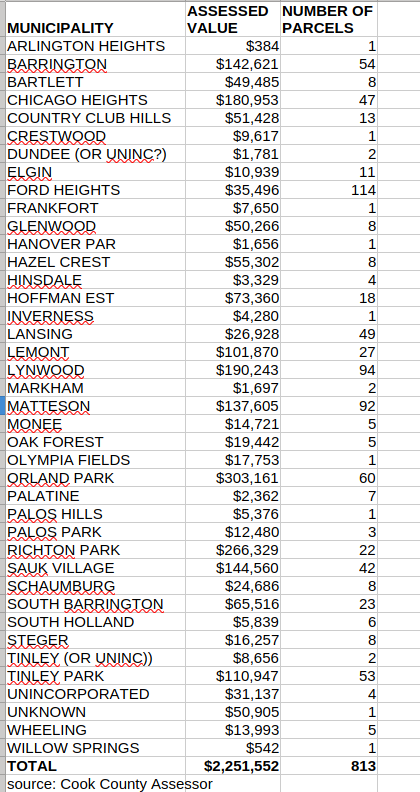

Countywide, the 813 class 239 parcels have a total assessed value of $2,251,552. While the Assessor’s records are imperfect (there being, for example, no “Dundee” municipality in Cook County), it appears that only 37 of the County’s municipalities (plus a few unincorporated areas) contain class 239 parcels. The tally is shown in the following table. Keep in mind that these are assessed value, 1/10th or less of the actual market value.

While class 239 is a great bargain for owners of “farmland,” the inequity doesn’t seem, by itself, to have a major effect on the financial condition of the taxing bodies. For example, Ford Heights has the largest number of class 239 parcels, 114. Total class 239 assessed value in Ford Heights is $35,496. If this land was subject to equalization like other parcels, the equalized assessed value would be $107,067. As noted above, the Assessor seems to undervalue class 239 parcels, but even if we assume undervaluation of 75%, the total EAV of these parcels would be $428,268, for a net increase of at least $392,772. (I say “at least” because some or all of the class 239 parcels may be assessed at less than $150 and therefore completely untaxed.) The latest report I can find for Ford Heights total EAV, from 2022, is $14,201,062. Thus, if my assumptions are correct, and tax levies don’t change, then the typical property owner would save just 2.76%, Longer-term, landowners might be encouraged to develop their parcels, with housing or other improvements, so the benefit over time might be greater and might not only be financial. There would be no expense to the Village or other taxing bodies.

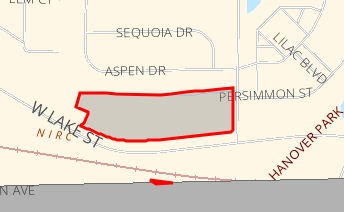

And of course the captioned illustration at the top of this post, 7+ acres in desirable Hanover Park, easy walk to Metra, adjacent to residential areas (or suitable for retail/commercial use), takes advantage of class 239 to pay taxes of less than $200/year.

[Still more to come.]