“Cook County assessor misclassifies hundreds of properties, missing $444M in one year alone,” says the Chicago Tribune. The report is joint with Illinois Answers. $444 million is a lot of money, about 1/2 of 1% of all the assessed value Countywide. And assessment data is public, so the journalists could easily find examples of inconsistencies.

Evidently, Fritz didn’t do as good a job as we wish. The journalists didn’t report any comparable error rates for other jurisdictions; perhaps they couldn’t find any. Some Cook County taxpayers were unpleasantly surprised when, the Assessor having suddenly discovered their improvements, they received big bills for back taxes.

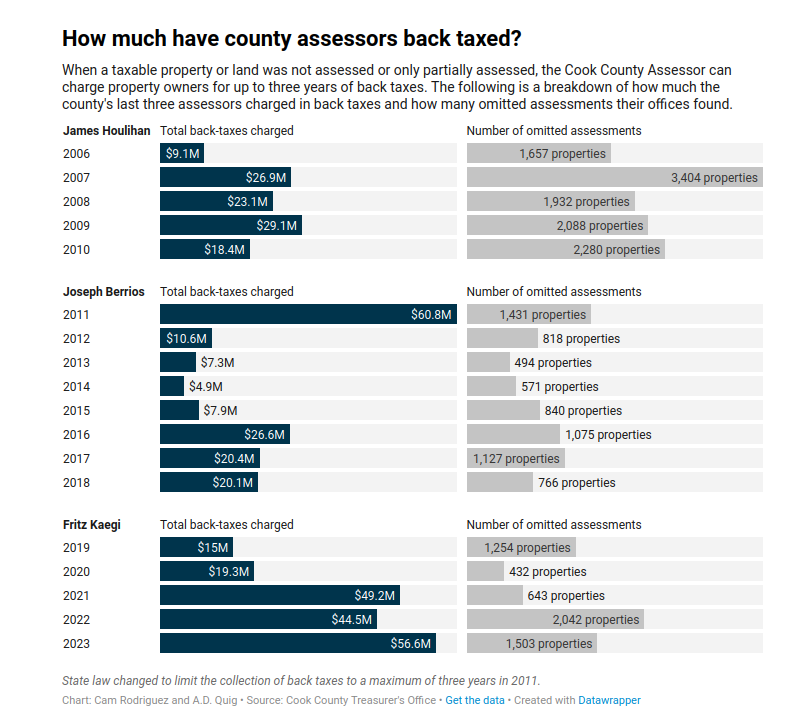

The report includes a chart showing annual number of improved properties discovered and amount of back-taxes billed for each year going back to 2006:

From this it appears Fritz’s record is pretty much in line with the results of prior Assessors. He says there are 1,864,161 taxable parcels in the County, so in his worst year he discovered missed improvements on 0.1% of them.

Note that the Tribune/IAP folks mislabeled the chart; the assessments probably weren’t “omitted,” but the properties were underassessed because improvements weren’t recognized.

The report includes a number of complaints by former County employees and some local officials, essentially agreeing that Fritz did an imperfect job. There’s even a time-series of aerial images of a subdivision in Lynwood, showing very clearly that houses have been built, but didn’t yet show up on the tax rolls. For a village of 9116 people, and their school districts, this subdivision of a few dozen houses might be a significant fiscal consideration. And for the new homeowners, the back taxes will be a burden.

(The report implies that in this case the ball was dropped by the Bloom Township Assessor, an intermediary between Fritz and the municipality. )

The journalists also start, and conclude, their report with the case of one property owner who has experienced serious tax increases and is considering moving out state. Yes, excessive and wasteful government spending, and high taxes, is a big problem here. But fixing assessment errors affecting 0.1% of the parcels will do little to address it.

We could make a couple of observations here.

What if Cook County could drop improvements from the tax base, assessing and levying only on the value of land, what the each parcel would be worth if vacant? Probably none of the problems described in this report could have occurred. And instead of increasing “the number of budgeted field staff from 34 in 2023 to 38 in 2024,” Fritz could have laid off most of the field staff, putting a few to the task of correctly valuing land. He’ll also need (probably already has) somebody to monitor the County Clerk’s Tax Map Department, to be sure parcel boundaries and numbers are up to date.

How does the government’s ability to accurately administer the property tax system compare to the income tax system, or the sales tax system? Nobody knows. While nobody really understands how income taxes work, the revenue agencies release only aggregate data, so we know nothing of any invidual’s situation unless the person chooses to publish her income tax returns, as some politicians do, or somebody violates the rules and liberates confidential information. Even sales tax information for individual taxpayers is largely confidential. To guess how well these taxes are administered, one could search for /IRS agent indicted/ on luxxle or freespoke .

And here’s a report asserting that over a recent 18-month period, more than 1% of Internal Revenue Service employees had “confirmed tax noncompliance issues.” (Apparently most of them kept their jobs.) If 1% of IRS employees are “cheating,” I doubt that the percentage for average taxpayers is less. So it seems that overall, Fritz is doing a better job than the Feds.

Maybe he should ask the State to make his job easier by removing improvements from the real estate tax base.