is subtitled “How it Moves and Why,” but this isn’t about the Kinetic Condos. It’s a response to a questions Georgists often hear: “If you’re so smart, why aren’t you rich?” Different Georgists give different answers, including “I am rich.”

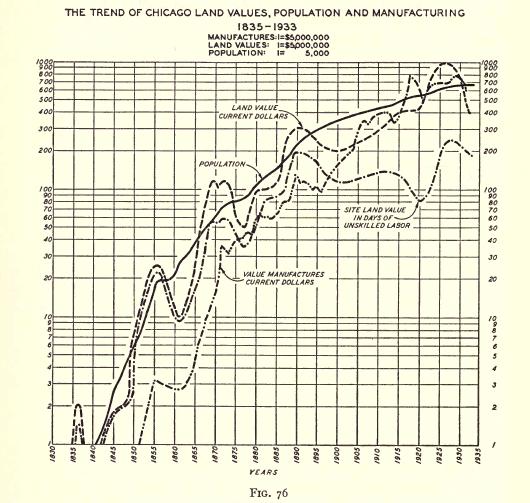

We know that the major cause of the business cycle is the capitalization and trading of government-protected privilege. This privilege can be any kind of income obtained without producing, and may flow from spectrum licenses, drilling rights, patents, copyrights, or a hundred other sources. But the main one is land ownership, since land is not a product of human labour.

When demand increases for a product or service, production can increase, but that isn’t true of privilege. The only limit on the price of privilege is what the market will bear without breaking. So can’t we measure that price, use the information to forecast economic meltdowns, and thus become wealthy?

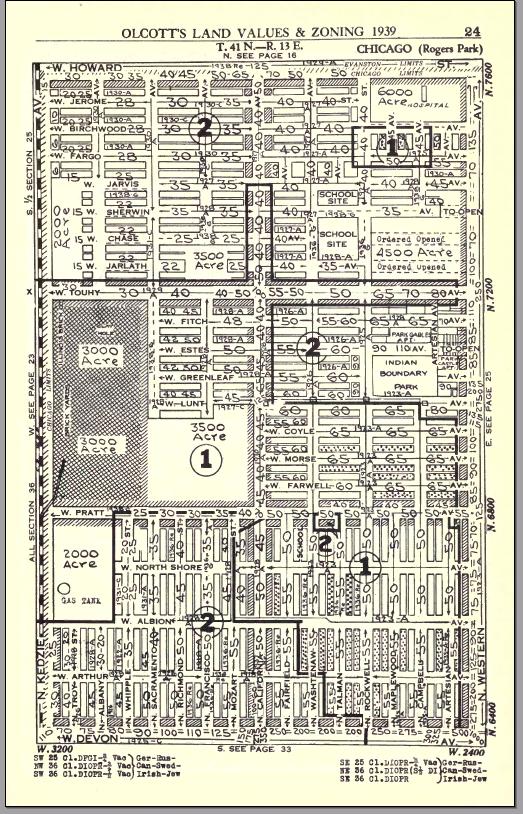

Our massive government statistics operations, which know how much more Asian-American households spend on rice than the rest of us do (4 times as much, as of 2003), and that people spend an average of 2.43 hours each weekday watching television, know just about nothing about the price of land. Only a few countries maintain any such information (Korea, Japan, Denmark, and Australia come to mind). Many local authorities compile land assessments, but the relationship to actual market prices is, at best, elastic, and the information is not systematically reported. So indirect and ephemeral indicators must be relied upon.

Moreover, they land price cycle tends to run about 18 years, and may be disrupted by war (not by much else, it appears). This means that taking advantage of it requires a great deal of patience and, one can only say, a certain amount of faith. And starting at a young enough age, by the way. Of course the cycle might be entirely abolished, but that would require the elites, and some of the non-elites, to surrender significant privilege.

The book is well-written, well-edited, and well-documented. (A subject index would be nice.) Economist Mason Gaffney’s review is far more informed than anything I could have produced. He points out a number of imperfections, but on the whole this is a very useful book for anybody who wants to know why many of us aren’t rich, or who would like to be.